She is walking alone behind the gnarled men of the village who have come to greet her with a big green satin banner that says, “May God Save Ireland.” She considers herself in the same business these days. Along the way the schoolchildren have lined up on both sides of the road, and the junior band, all apple-cheeked and scrubbed for the biggest day this tiny place has seen in perhaps centuries, is playing tin whistles in a rousing Presidential Salute. It is a tableau of tradition and timelessness in the Irish countryside except that it has never happened before and would not have but for her.

She has come at the invitation of the women — to honor them and their efforts to hold body and soul together in this largely forgotten dot on the map in the far west of conservative Catholic Ireland. She herself was born and reared in the nearby town of Ballina, and she understands what for so long has been unspoken. It is the women of the Ladies’ Association who actually run things around here in rural Carracastle, County Mayo. They must make do for their families in a dramatic, underdeveloped landscape of seaside cliffs and misty bogs, a land of long depressing winters and scarce jobs, ravaged by emigration, where government services seldom reach. But no one has ever acknowledged the Ladies’ Association before. Now it is almost too much to bear that on the occasion of its twenty-fifth anniversary the president is taking notice, and that the president is a woman herself.

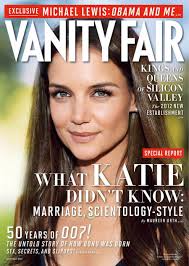

“She’s here, ladies, and she’s walkin’!” cries the first village woman to spy President Mary Robinson as she approaches the small Community center, crammed with people in their Sunday best. She steps across the red carpet laid out for her and makes her way to the stage amid whistles and cheers. Robinson’s bearing is naturally regal; tall, tawny-haired, a perfect size 8, she is chicly turned out in a long green jacket paired with a short navy skirt. But even now, in these confident glory days, there is still a certain awkwardness to her gestures that betrays an ingrained shyness– she frequently presses the backs of her knuckles together and constantly nods her head up and down. For the villagers, however, Mary Robinson’s mere presence is a celebration of gender, of heart, and of the Irish spirit.

“To me this is the face of modem Ireland, and a community that is developing its own self-reliance, its own strengths, and that is very much providing the care and the services and looking after old people, looking after those who have special needs in the community,” the forty-eight-year-old mother of three tells her audience in a throaty contralto that carries the polished tones of the boarding-school top girl she once was. “I have great pride going around the country and seeing so much of this kind of self-development.”

“Every woman in the village voted for her,” a mother of seven tells me. “A woman has to do her job ten times better than a man to be acknowledged,” says a schoolteacher from nearby Castlebar who was presented an award by the president for her work with children. “It’s easier now to come forward because of Mary Robinson.”

“We’re very isolated,” says a third woman, who lives in a small town outside of Galway and helps publish a newsletter for women’s groups in western Ireland. “Women are considered tea-makers and childminders. She makes men look at our input. She’s mentioned [the newsletter] on two TV interviews, and when she mentions us it’s euphoria.

Indeed, as time goes on — Robinson is now in the second year of her seven-year term — it doesn’t seem to matter much that the presidency of Ireland is largely a ceremonial role or that she is enjoined by the Irish Constitution from speaking out or participating directly in politics. She campaigned to change the office, which has long been viewed as a sinecure for retiring mule party leaders. “We talk about the president not having power, but she is very important for empowering,” says the noted Irish poet Seamus Heaney, who has known her for years. She represents, proclaims poet Paul Durcan, a move away from the last decade’s preoccupation with “the gun, the altar, and the credit card.”

The Irish have never seen anything quite like Mary. She’s a little bit of Havel and a little bit of Hepburn. Once a radical crusader, she’s now the country’s most prominent self-esteem therapist, the moral force who embodies, says Heaney, “the new secular modern Ireland.” To govern, she gets down on her knees, not to beg or to pray but to put her ear to the ground. “I’m a Catholic from Mayo” is how Robinson has described herself — as if the arc of her former career as a liberal senator and human-rights attorney weren’t in direct conflict with the church and many rural Irish traditions.

“She told me, once, she saw her role as being ‘quietly subversive,’ ” says a friend, Lewis Clohessy. “The Constitution is there, but there’s no doubt she pushes the envelope out,” adds Robinson’s brother Henry Bourke, a barrister. “If I were a politician, I would want to use her in the nicest possible way. At the same time I’d keep a sharp eye on her.”

“I feel I can change perceptions about equality,” Mary Robinson herself tells me when we meet at her residence. “This office allows me to be more symbolic, more reflective, to engage in lateral thinking, to do the unexpected.”

In her quest to redefine the, Irish presidency she has also transformed herself. The Mary Robinson of today, who sifts distinguished invitations to speak from all over the world, who in July is opening the four-day meeting of the Global Forum of Women in Dublin, is far more glamorous and outgoing than the Mary Robinson of old. And yet much of her power seems derived from an unrehearsed quality. “The Queen of England’s smile is a ceremonial smile,” observes Heaney. “Mary’s smile comes from a slight anxiety . . . that says to people, ‘I’m here, I’m your president, I’m also a previous self.’ Some of her authority is mixed up with her candor.”

The real challenge was to redirect her passionate, if legalistic, oratory into a new language of symbols and poetic allusion that would neatly sidestep political minefields. Gone is the firebrand who in an unguarded moment during the election campaign told Hot Press, Ireland’s Rolling Stone, “The whole patriarchal, male-dominated presence of the Catholic Church is probably the worst aspect of all the establishment forces that have sought to do down women over the years,” and went on to charge that the Irish government didn’t “give a shit” about the émigres.

Robinson was twenty-five in 1969 — the youngest woman in the history of the Irish senate, the first female professor of law at Trinity College in Dublin — when she boldly introduced legislation to legalize contraception. It wasn’t until 1973 that she actually got a hearing on the subject. For years afterward she also got obscene letters and used condoms in the mail. “That taught me, if you believe in something, you must be prepared to pay the price,” Robinson says. How utterly satisfying it must be for her now to realize that, at the very moment she was being vociferously attacked by the Catholic hierarchy for introducing the contraception legislation, the popular Bishop Eamonn Casey, late of Galway, was having unprotected sex with a young Connecticut woman whose family had entrusted her to his care. The recent scandal rocked the Catholic Church in Ireland to its very core as the beleaguered, if not bemused, citizenry learned that not only is the bishop the neglectful father of the woman’s seventeen-year-old son, he had also paid her more than $100,000 from church funds.

As the bishop abruptly resigned his post and fled the country, it was impossible not to be further reminded that Robinson herself has always been fearless in the fight. As each new obstacle loomed, she attacked back with intellectual abandon. She championed and won rights for gays and for children born out of wedlock; got women the right to sit on juries, and eighteen-year-olds the right to vote; broadened the concept of legal aid, and shrewdly superseded the paternal hierarchy of the Irish legal establishment by taking equality cases to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. “Irish people hate conflict,” observes screenwriter Eoghan Harris, one of Robinson’s media advisers during her presidential campaign. “Mary Robinson is comfortable with conflict.”

Robinson has also achieved what no American female politician has been able to: she caught the ear of the women with her feminist beliefs, and now even the men are listening. The First Citizen, as the Constitution calls her, is criss-crossing Ireland with the message that feminism should be an inclusive, humanistic social tool and not, as she very politely but firmly characterizes much of American feminism, “exclusive” – “a rather hard-line approach.” She wants to strengthen the family, to place a higher value on the image and work of women who, for whatever part of their lives, stay at home, contribute to their communities in volunteer efforts, and learn in the process new ways to solve problems: “We’ve gone beyond the stage of simply wanting more women in particular positions . . . It’s much deeper than that and much more fundamental.” During a visit to Brown University last fall, Robinson asked, “By focusing our energies as feminists on encouraging women to ‘achieve’ a more ‘significant’ role in society, are we not to an extent perpetuating the oppression of women?” When I spoke to her, she rephrased the query only slightly. “If feminists don’t value the work of women who stay at home, how is society going to value it?” she asked. “I would be very strongly supportive of men having much involvement in child rearing and homemaking.

The whole country was tuned in when the major TV channel aired a speech Robinson gave recently at Trinity. “In a society where the rights and potential of women are constrained, no man can be truly free,” she said. “He may have power, but he will not have freedom.

“Equality between the sexes is seen to be a woman’s issue,” she said. “It is not. It is said to be a marginal issue. It is not. It is perceived as a threat to the traditional structures of a society and it is not.”

The following day she remarked that she was “almost taken aback by the intensity of listening.” And no wonder. The nation that listened so carefully to Robinson that evening is, writes philosopher Richard Kearney in Letters from the New Island, engaged in “nothing less than a national psychodrama. A play between opposing parts of ourselves — one part that longs for tradition, security, continuity, and another part that wants to come clean, to break the old icons in the name of something different.”

“So many Irish are utterly heartbroken and frustrated about their failure to actualize their potential, although they won’t admit it,” adds the writer John Waters, whose nonfiction best-seller, Jiving at the Crossroads, gives a poignant account of stifling small-town Irish life today. What brings them down, Waters tells me, is “begrudgery” -identities and roles that are so firmly fixed at birth that in a town of two thousand, for example, there is such a rigid hierarchy that “I know my place almost to a number – I know how many people are above me and how many below. That’s why Irish people go to America and become millionaires. If they stayed in Ireland they’d become alcoholics . . . Mary’s breaching the codes of respectability — she knows that the Irish people are tired of being afraid of their neighbors, and she knows they want to change.”

Robinson’s whole modus operandi is high-concept, high-symbol. To the Irish, who are used to moving through a society in which behavior often contradicts the rules, she too is communicating against the grain, but often nonverbally or in code. One of her bodyguards is a thirty-year-old woman named Anne Higgins, a high-spirited, pistol-packing — 36 Smith & Wesson — blonde who could have stepped out of a James Bond movie. Because the president doesn’t like daises — linear and patronizing — they’ve all but disappeared at official functions, replaced by round tables. And all of Ireland knows that in her kitchen window Mary Robinson keeps a light burning day and night in a vigil for the millions of Irish, most of them educated beyond their country’s ability to employ them, who have been forced to emigrate.

Her timing is perfect. “We’re the most exciting country in Europe now,” says Noel Pearson, the producer of My Left Foot and the Abbey Theatre-to-Broadway hit Dancing at Lughnasa. The Irish cultural boom encompasses everything from U2 and Sinead O’Connor to films like The Playboys and The Commitments to Heaney and Durcan. “The chains are off. We’re not a part of Britain, we’re part of the European Community, and that’s the most important thing that’s happened in twenty years,” Pearson adds. “It’s sexy to be Irish in America today — it’s fashionable all of a sudden. All this deprivation is over, and Mary Robinson is part of it.”

Except for one thing: Ireland’s agitation over sex. In February the country confronted the case of a pregnant, fourteen-year-old rape victim — a girl reportedly so uninformed about sex that she had no idea she had even had intercourse until she became pregnant. Irish health professionals concur that such ignorance among the young — the girl apparently did not know the difference between anus and vagina — and even among some adults is not at all unusual. May brought the disclosures about Bishop Casey, one of Ireland’s best-known prelates. Revelations of his sexual transgressions have not only unleashed a flood tide of talk about all manner of Irish priests and bishops breaking their vows of celibacy but also undermined the church’s moral authority at a crucial moment. But then, church and state in Ireland have always seemed locked in a mad tango. During Ireland’s brutal struggle for independence from Britain, with its official Protestant religion, Irish nationalism fused with Catholicism: sexual issues which might wise have been open for debate symbols of national identity. Besides, no matter what horrors occurred, there was always confession.

“As a result of 150 years of severe sexual repression, sex is the key to the Irish political revolution,” observes Eoghan Harris. On the eve of the millennium, an entrenched set of laws governs a populace that regularly breaks them with the old nod and the wink. For all intents and purposes abortion is illegal, but incest is fairly widespread. There is no divorce, only a lengthy, complicated process of separation. It wasn’t until 1979 — thanks in large part to crusades Robinson kicked off — that the Irish legislature legalized contraceptive use for married couples, and then only for “bona fide” family-planning purposes, with a doctor’s prescription. Charles Haughey, the health minister at the time, declared the new law “an Irish solution to an Irish problem.” Today condoms can be legally purchased only by those over eighteen, in pharmacies or at approved family-planning clinics.

“If we don’t have divorce, we can say marriages don’t break down,” comments a Dublin psychiatrist who counsels women who have had abortions. “If we don’t have abortion, we can say there is no abortion problem; if there’s no contraception we can keep this sexual revolution at bay.”

Robinson understands the historical context. “It can’t be underestimated — there is a defensiveness, a lack of security about ourselves, that comes from our colonial past,” she says, referring to the almost eight hundred years of British rule of Ireland. “Law was foreign law for a very long time,” she points out. “So there well may be a certain sense that if the law doesn’t comply with your values you can have a law on paper and be doing something else.”

But Ireland has twice recently got caught. The more serious of the two scandals is the highly publicized case of the fourteen-year-old girl, allegedly raped by, the father of a friend. The girl’s parents had taken her to England for an abortion, but were summoned home after they contacted Irish authorities about using fetal tissue as evidence to prove the identity of the father. They were answered with injunction from the attorney general, prohibiting the girl from traveling abroad for an abortion. But her subsequent threats of suicide prompted the Irish Supreme Court to reinterpret the Constitution’s “copper-fastened” amendment against abortion for the first time finding that the right to life of the mother had to be considered. (The girl then went back to England and had an abortion, as do five thousand other Irish women each year.)

The sex scandals have hit as the Irish are being asked to approve the Maastricht Treaty, which would guarantee their full membership in the European Community. Per Ireland’s special request, the treaty carried with it a “protocol” – the Irish ban on abortion. Now, in light of the Supreme Court ruling, the ban is no longer the law of the land. Just to complicate things even further, to prevent undue delays the E. C. Council of Ministers refused Ireland permission to amend the offending protocol. What to do about the right to travel for abortion and the right to information about abortion, which are guaranteed by the E.C., but not permitted in Ireland, also needs to be resolved. The situation is explosive and changing daily. In late May the distributors of The Guardian opted to withhold an edition carrying an advertisement for a British abortion clinic rather than break the law. “Will the radio waves be censored? Will we burn books after we have finished impounding newspapers?”

Both anti- and pro-abortion factions demanded that the law be clarified before the scheduled treaty vote on June 18. But the government of Prime Minister Albert Reynolds refused; the last referendum on abortion, in 1983, was hard-fought, bitter, and divisive. Hanging in the balance are putative billions in E.C. subsidies, not to mention the whole future of Ireland, which for so long has gone along with the church in theory but actually lives by its fabulous oxymorons; the Irish way of coping with unyielding Catholic doctrine, suggest the Dublin psychiatrist, is to view its tenets as “aspirational absolutes.”

Mary Robinson chooses to see all this Sturm and Drang as healthy. “There’s no good in the new Ireland,” she says. “The new Ireland takes on board the anguish and difficulty of this [rape] case . . . . There isn’t a person who isn’t involved, and, in its own way, I think that’s very good.”

When the case broke Robinson went right up to the edge of her constitutional limit on speaking out. Instinctively, when she chose to intervene, she did not use the familiar legalese or the hollow rhetoric of the back-room and barroom corridors of power. Rather, she said, “I think I am in a very good position to know what hurt, bewilderment, to know of the anxiety, of the sense of frustration, of the sense of helplessness . . . . We must move on to a more compassionate society. . . . I hope we have the courage, which we have not always had, to resolve.”

“These windy politicians, when they open their mouths it’s such a pollution of language,” says Irish novelist Francis Stuart. “She spoke the language we speak to each other now.”

Robinson’s statement galvanized the left and startled the right. “It makes what I’m trying to achieve that little bit more difficult,” says the chairman of Ireland’s Pro-Life Campaign, Senator Des Hanafin. “She’ll cause trouble yet. Of that I am certain.”

Conflicts like this one have forced Robinson, once referred to as a “smoked-salmon socialist,” out from behind the “thicket of the law.” “As a lawyer, I held back. It’s not good as a lawyer to become emotionally involved with your client,” she says. Her baptism of fire was her long campaign in 1990 out in the countryside. “I needed for my own sake to get away from law courts and the practical precision of arguing cases before the courts, of being sure of my facts.” Instead she was thrown into “the messier, more untidy world,” and switched her influences accordingly. “She’s reading poetry now instead of legal briefs,” says the Irish politicians and poet Michael D. Higgins, who twice served as a Labour Party senator with Robinson. (“Thank God Yeats has been dead for fifty years,” she has joked. “Otherwise he might sue me for copyright infringement.”) I remember clearly the transition from a black-haired young woman to a person who had been through the mill, who was the constitutional lawyer gone gray,” says Higgins. “She opens herself up to all those areas of hurt she didn’t touch as a lawyer, when she was protected by legal formality.

And she is opening Aras an Uachtarain, her palatial official residence a mile and a half from the center of Dublin, to those who represent some of the country’s most intractable problems. Nothing is more painful than the bloody division between the North and South in Ireland, yet Robinson is able to build bridges to the North that others can’t. She is a Catholic married to a Protestant, political cartoonist turned lawyer Nicholas Robinson, and she resigned from the Labour Party in 1985 partly because she felt the pro-British faction in the North was not being heard. She is the first president ever to invite Protestant and Catholic housewives from the strife-torn Belfast to a get-together at the presidential residence to meet their counterparts from the South.

Before becoming president, Robinson had never been to the grand quarters and gardens of “the Park,” where Queen Victoria stayed when she visited Ireland and where Winston Churchill played as a boy. The Robinsons and their three children – Tessa, twenty; William, eighteen; and Aubrey, eleven – were overwhelmed by its grandeur. When they first moved in, Aubrey asked his mother, “Why are we whispering?”

From the moment I land in Ireland I find no one who isn’t just wild about Mary – her latest approval rating is 87 percent. Says Seamus Heaney, “There’s a sneaking, surprised pride in the electorate that they put her there.” Such is their devotion than an Irish soldier was severely reprimanded one day for joking “Big Bird has landed” when Robinson arrived on the scene wearing a yellow suit. “She was just named to the list of the world’s best-dressed women, y’know,” the customs agent at the airport volunteers. She’s Ireland’s new philosopher queen and the toast of Dublin, often behaving more royally than that family on the nearby isle. But not so long ago Mary Robinson was definitely uptight. Despite her brilliant career, she had never made it onto an Irish Cabinet or gotten elected to the Dail, the lower house of deputies, where power resides. She was an ultra-serious, radical constitutional barrister saddled with the distant public personality of a starchy academic. A pickle, “She was wheeled out when there was a debate on a question nobody could understand,” say Brenda O’Hanlon, her former campaign coordinator, “definitely not somebody you’d want to go out with at night for a couple of drinks.” Childhood friends remember Mary with affection as “popular” but “gauche,” “a lump of a girl.”

She would wear long, shapeless barrister garb “like reverend mothers,” says O’Hanlon. She one had her unraveled skirt hemmed in the back of a cab on the way to the Strasbourg court by one of the women she was representing in a landmark case. The two times she ran for the Dail “she was a hopeless campaigner,” according to Dick Spring, the head of the Labour Party, who later nominated her for the presidency. “In one campaign she breast-fed one of her children [in private] in a working-class district and people were appalled,” he says. Spring had disappointed Robinson when he passed her over for the Cabinet post of attorney general in 1984. “It would not have been well received among her peers,” he explains. “She wasn’t a team player within the parliamentary system. She rubbed people the wrong way a lot.”

She was known as a technical lawyer with a flair for the micro who combed the codes for injustices that could be righted. Her colleagues claim she stood on haughty principle. “I could never see Mary [defend the accused in] a rape case,” says John Rogers, a former attorney general. “Mary is not a person for the gray areas.” Nor did she waste any time being chummy with her peers. “You didn’t ask her for help,” says a younger woman attorney. “She was a prenatal bluestocking,” says a man who has known her for years.

Moreover, her shimmering credentials — finishing school in Paris, highest academic honors in law at Trinity, graduate school with honors at Harvard — were an enraging rebuke to male superiority. “Senator, professor, Mary Terese Winifred Robinson,” Patrick MacEntee, one of Ireland’s most famous legal lights, used to bellow in mockery. “B.A. (Mod.), T.C.D.; LL.M.; etc., etc., etc.” In Dublin they still can’t get over the fact that she once wore pants in the august Law Library, where barristers headquarter.

Today, “she can practically walk on water,” says Spring. But skeptics remain. I think Mary Robinson, if you knew her well, would give you the biggest pain in the ass you ever had on a person-to-person basis,” says a former official of Fianna Fail, the predominant political party. “But I think she’s unbeatable as long as she’s there,” he concedes. “Perception has become reality.”

And in a very short time. “Mary Robinson became president and I got a designer frock,” says Nell McCafferty, whose name in Ireland is a virtual synonym for radical feminism. “I gave myself permission – ‘Fookin’ A, she looks good and we can relax now.’ I got myself gold earrings, my hair dyed — I got the lot. I went to a nightclub and I had a ball.” But isn’t Mary Robinson wasted up there in the castle, a woman with her intellectual prowess, unable to speak out? “Nooo,” says McCafferty. “She’s already laid all the groundwork — she’s in a much better position to expand now. Her every speech is reported, the power of her every word is reported. That didn’t used to be. She’s got power now.”

On a brilliant spring afternoon Nicholas Robinson is seated in what was once the ballroom of the British viceroy’s residence. Reserved and handsome, bearded and tweedy, he emanates the merest hint of a twinkle as he talks about his wife. He and the former Mary Bourke have known each other since their undergraduate days at Trinity, which was then considered such a Protestant stronghold that she needed special permission from the Catholic archbishop to attend. Currently on leave of absence from the Centre for European Law at Trinity, which he and Robinson co-founded, and chairman of the Irish Architectural Archive, Nick Robinson is exactly what every hard-driving head of state needs; a great wife. “I’m quite happy to simply make the analogy to the countless able women who have put their support behind male political leaders,” he says. “If they can do it, why shouldn’t a woman expect the same from her husband?”

“I think he is an extraordinary man to have put up with his wife — it’s very difficult,” adds Robinson. “We are very close friends. I think our friendship is one of the most important things. He’s a very emotionally strong man. He’s a very secure man. He’s a very loving man.”

When asked to account for his wife’s own strength of character, Nick Robinson says, “Her family background.” The five children of Tess and Aubrey Bourke, both doctors, arrived within six years, and Mary, the only girl, was reared no differently from her brothers. “I grew up in an environment of total equality,” she marvels. “That was something that my parents never talked about.”

“She grew up unquestionably a tomboy,” says her brother Henry, a barrister in Galway. “It was ‘Fight your own battles and fight them hard or be swallowed.’ She learned to take hard knocks and stand up for herself. She certainly whacked me hard.” Says her father, “There was one way to hold her own and that was to use her teeth.”

It was Mary’s fortune to be born third, sandwiched between Aubrey (who died of cancer in 1986) and Oliver, major jocks who became doctors, and Henry and Adrian, major party boys who followed Mary into the law. The younger brothers, especially, were both social and sporty; all five Bourkes were very bright — but Mary was the true intellect.

Although Mary’s mother, the late Tess O’Donnell Bourke, of Donegal, gave up medicine when the children arrived, she had a sister who was a doctor. “There was a tradition of professional women in that family,” says Nick Robinson. “Most women here are brought up to have no sense of that — men become professionals and women don’t. Mary was encouraged at every stage to strive for what she wanted.” From an early age she seemed to know what that was. In childhood games, says her brother Henry, Mary often cast herself as Robin Hood. “If we played cowboys and Indians she preferred to be the Indian, the underdog.” Henry also remembers her willfulness. She once dragged her two younger brothers, seven and six, on an eight-mile hike to the next town because she so resented her mother’s telling the children to get out of the house and go for a walk. “She would argue her point from a young age, more so than any boys. She would take our parents on in nicest possible way,” he says.

“She also had the example of work in the medical world,” adds her father, who has practiced medicine in Ballina for fifty years. “I practiced every day and I didn’t take holidays or weekends.” Dr. Bourke, known as a “physician to the upper crust,” also saw patients who paid with fish or a cart of manure for the garden. “I think she learned from him a great deal about the innate dignity of people,” says Nick Robinson, “the capacity to talk to them at the right level.”

At the same time, the Bourkes known as standoffish — the well-to-do, educated family in the plain little town on the river Moy, a famous, unspoiled salmon-on-fishing mecca in Mayo, one of the westernmost counties (the next stop, they say, say, is Boston). Dr. Bourke was descended from old landlord stock. The children went to a private school, had a pony named Billy Boy, and played in an enclosed garden across an alley from their large, three-story cinder-block house. “Some people said they had a walled-garden mentality, recalls Loretta Clarke-Murray, who runs a general store in Ballina.

It was the forties and the fifties, and Ireland was in a cultural and political stupor, says Henry. “It was just dead. Nothing moved. You were content with your own. You never looked over the parapet.” It took the election of John F. Kennedy in America to wake everyone “He came to Ireland and brought us glamour and charm,” Henry says in a kind of ironic echo of what the Irish are saying about his sister today. “We suddenly felt we were a people to be reckoned with. Our man had made it to the top,” he exclaims. “You could feel the changes from the fifties to the sixties.”

Yet in that part of the country there was never any escape from history. The great potato famine in Ireland that began in 1845 is still as fresh as new-sown spuds in many Irish memories. In nearby Westport there still stands a dock where the British landlords stored and shipped corn for export even while the Irish who had farmed it were dying of starvation.

Mary’s model for justice was her grandfather Adrian Bourke, a solicitor in Ballina who impressed upon her that law was essentially about justice for the small guy. That may seem very obvious in some circles, but it wasn’t that obvious in western Ireland when I was growing up. He was a man of few words, but they were all dense with this sense of law being an instrument of justice and of social change.” Yet he was definitely not an iconoclast, she adds. “He was a religious man and a conservative man. But he had a radical sense of what law was about in achieving justice for the individual.”

As children, the three younger Bourkes would often wander over to the courthouse “and sit all day in the balcony area looking down at the cases day in and day out,” Henry says. “From very early on it was taken Mary would go into the law.” She would be given every privilege of education possible, and, to prepare her, sent off to boarding school. Tess Bourke always had big plans for her only daughter. First it was the exclusive Mount Anville in Dublin, run by the “Mesdames” of the Sacred Heart. Then Mademoiselle, Anita’s, a fancy finishing school in Paris, so Mary could get her French.

When Mary came back to attend Trinity with her brothers, Tess went looking for a house for them to share. She found and bought the one Oscar Wilde was born in and installed the children’s old nanny to look after them. In the mornings, the nanny would set out glasses of milk at the top of the stairs; all five Bourkes would race down, gulping, and leave the empty glasses on the windowsill as they ran out the door.

Senator David Norris recently commented that Mary’s two older brothers went to Trinity “to play Rugby,” her younger two “to party,” and she alone went to learn. “We took it a bit more casually than she did,” says Henry in a drastic understatement. One night the boys filled the bathtub with every known liquor, and a visiting American professor passed out in it fully clothed. “I got a letter from Mary once datelined ‘Wilde House,’ ” says Dr. Bourke. “It was meant to worry me, and it did.” “The difference between us and Mary,” says Henry, “is that she’d come to the party, but if she had a lecture at nine the next morning she’d make it.”

After winning practically every academic honor at Trinity, Mary went to Harvard on a scholarship for a year’s graduate work to get her master’s in law. Harvard in 1967 was a revelation that not only marked her for life but also deepened her belief that the law is essentially an instrument of change. “Law students weren’t going to the top law firms on Wall Street, because they were going into federal poverty programs and civil-rights movements in the South and so on,” she recalls. “It was the first time I had been challenged by a society openly questioning its values.” She stubbornly clung to this outlook and came to call it her “Harvard arrogance.”

Once she was back home the personal became political. Mary’s parents did not want her to marry a Protestant. “I had to make a choice and fight for my choice,” she says. Mary Bourke was convinced Nick Robinson would always be there for her in whatever she undertook. “I remember him presenting me with an orchid when I was going in to do my exams in the Kings Inns [legal society],” she says. “I think he was mocking me but also supporting me with this magnificent orchid. And he was also daring me to wear it — which I did.”

“He was always mad about Mary,” says the poet Eavan Boland, a close friend. Says Henry, “We should have seen it coming.” But they didn’t, and when Mary announced her determination to marry Nick, her family did not attend the Dublin wedding. “We rowed among ourselves about it,” says Henry. “She was bloody good about it.” Mary, who surprised her fellow feminists by taking her husband’s name, was given away by a barrister friend.

“At first we were a mixed marriage, her family didn’t approve,” says Nick Robinson. “But literally within a few weeks everyone was quite happy. It was simply a question of advising her against it, but once done, the situation was immediately accepted, and we’ve got on ever since.”

Even before Mary, friends say, Nick Robinson saw the presidency as a possibility for his wife. “She could never have gotten through the campaign without him,” says Brenda O’Hanlon. Or without the savvy Bride Rosney, her closest confidante and political right arm, a former high-school principal who missed her calling as a field marshal. Rosney says that within two months “I knew the presidency was there for the taking.”

Robinson had never sought the office, of course, and she was completely unprepared when it was offered. But a photo of her celebrating a Labour victory with unadulterated glee some years before had stuck in the mind of John Rogers, the former attorney general and confidant of Labour head Dick Spring. “You never get good at politics, you know, until you win,” says Rogers. Labour wanted to increase its measly 9 percent representation in Parliament, and Robinson was the option who represented excellence, who he knew always went all out whenever she decided to undertake a cause. Rogers called on her at home on Valentine’s Day 1990. By then Robinson had left politics altogether and — ahead of the curve, as usual — was a highly successful senior counsel in the burgeoning specialty of European law. Why should she disrupt her practice and her family and go back in to pursue an impossible dream? Winning was out of the question. By the time she had retired from the Senate in 1989, after serving twenty years, politics had soured for her.

“ ‘That’s all very fine, Mary,’ ” Rogers remembers saying, “ ‘but you have served before and you will serve again’ There was a point when her face actually collapsed and she was shaken to the core by this idea.” She went to the Constitution to read the definition of the job. What persuaded her to run was the part about being the guardian of “the welfare of the people.”

Enter Eoghan Harris, a highly controversial master manipulator of TV images who talks like C-SPAN on acid. Unsolicited, he sent Robinson a detailed letter: “My view is that you can win the campaign,” he wrote, “by presenting yourself as a democratic rather than a liberal candidate and never as a liberal-left candidate.” Later, he followed up with a crucial memo — she was lousy on television and badly needed a warmer image. “Mary must come across as a person who would make a great president. The Dublin 4 subtext question: Why? Because she has the brains for it” (Dublin 4, taken from the Zip Code, is the Irish version of the liberal media-lit-pol elite.) “Plain People subtext question: Why? Because she has the beauty for it — she’d make us look good.”

He euphemistically told her there must be a “strong feminine factor.” Rationalizing that she was going on a job interview for six months, she submitted. Her hair was highlighted, cut, and permed, she wore makeup for the first time, and suddenly you noticed that she had great legs. With her husband at the wheel, she hit the road in a van, blasting Simon and Garfunkel (“Koo-koo-koochoo Mrs. Robinson . . . Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you”). Such was her sense of dedication that, once, when she discovered she was going to bypass a small pub in order to appear at another down the road, she walked back two miles in the driving rain to be there. When she arrived, she found one customer.

Meanwhile, back in Dublin, where the big boys of Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, Ireland’s two leading parties, were fielding their own candidates, not enough notice was taken of the woman who wanted to be president. “Nobody in Dublin knew what the hell we were up to,” says Brenda O’Hanlon. “Before they realized, it was too late.”

In the last days of the campaign, rumors were planted that Nick Robinson was being paid to stay around until the election — the marriage was over. A Fianna Fail member of Parliament also tried to smear Robinson as having been a neglectful mother. It didn’t work. “Mary, I defended your honor on the radio today,” a right-wing barrister told her shortly after the smear had hit. Robinson deadpanned, “What was said must have really been appalling for you to defend my honor.”

Meanwhile, the honor of the leading candidate, Cabinet minister Brian Lenihan of Fianna Fail , was besmirched by reports that he had allegedly attempted to inappropriately influence the president. Lenihan was unceremoniously sacked from the Cabinet. “So here you were, offering a presidential candidate to the people who was not fit to be a minister,” says pro-life senator Des Hanafin (who was recently expelled from Flanna Fail because he refused to support Maastricht). Such are the paradoxes of Irish politics, however, that for a short time it appeared Lenihan would actually be swept into office on a sympathy vote. But in the end the old politics-as-usual proved unacceptable — to Irish women, is particular. Mary Robinson ascended. She had taken a leap, and so had they.

Robinson’s activist presidency has marked a moment of redefinition in the soul of Ireland. “She managed to break with the stereotype of Mother Ireland as dispossessed, weak, forlorn, lachrymose, who calls upon her sons to sacrifice themselves through blood sacrifice so Mother Ireland can be redeemed again,” says the philosopher Richard Kearney, who helped Robinson with her inaugural address, As a result largely of British colonization, “that was the curious personification of Ireland — the mother calling her sons to die. She was passive, she didn’t intervene. She was a ravished, dispossessed woman.”

But not anymore. “With Mary Robinson,” says Kearney, “we’re into a revision and a whole reimagining of Ireland as a sister, as a modem woman.” Hail Mary.

No Comments