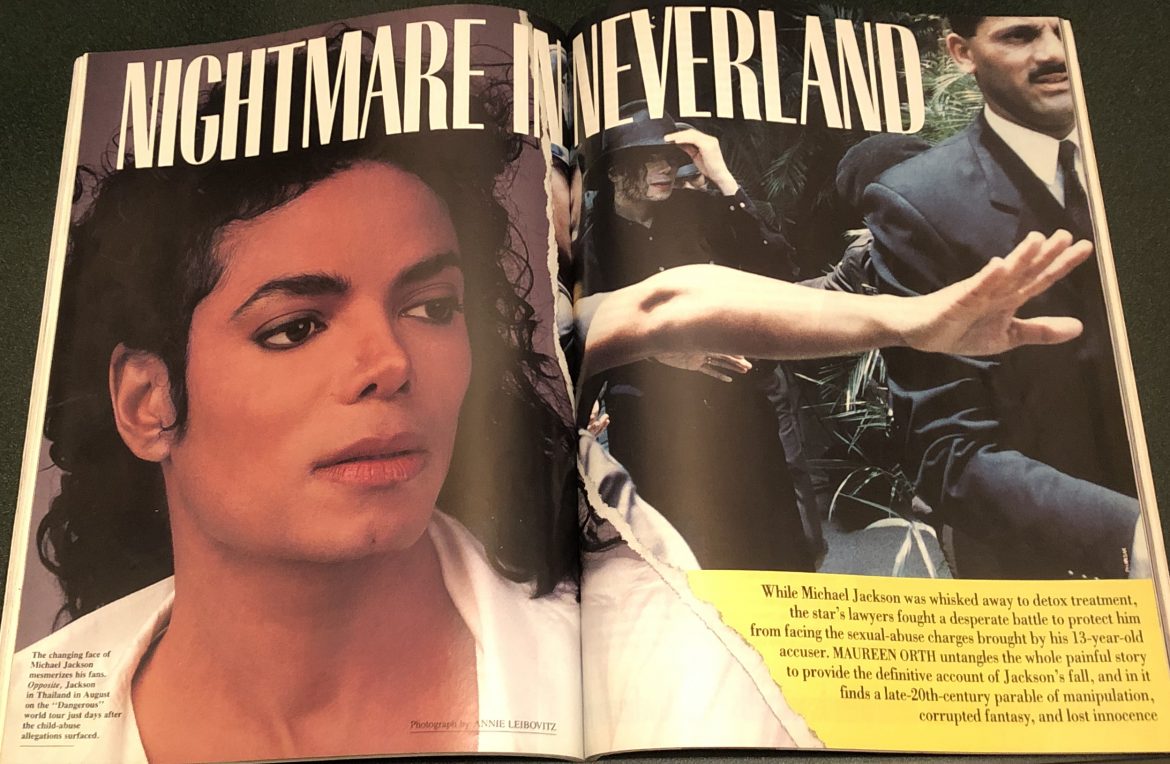

Vanity Fair – January, 1994

The tarantulas were out, crawling under the firefighters’ boots. Overhead, planes were swooping down low between the ridges, dropping streams of bright-orange flame retardant. As the raging fires threatened to reach Neverland, Michael Jackson’s 2,700-acre fantasyland, moguls who owned neighboring ranches were up on the hillsides straining to see through binoculars. Hours earlier, the exotic animals from Jackson’s private zoo had been evacuated. At any moment, a capricious ill wind could send everything up in flames. Neverland, like Michael Jackson himself, who was thousands of miles away on his aptly named “Dangerous” world tour, was feeling the heat.

In August, a 13-year-old boy had accused Jackson of sexual molestation, charges he vehemently denied. By the time of the fire in October, he was canceling performances right and left for various maladies, but his lawyers were promising he would nevertheless show up to be questioned. In November, the encroaching criminal investigation, the civil suit brought by the boy, and the nonstop screaming headlines shattered the fragile pop idol’s image and his grip. On November 12, cutting short his tour, he abruptly fled Mexico for a secret drug-treatment location, touching off shocking reports—missing medical records, a disappearing witness, a telephone call from Jackson in Switzerland to a friend who said the star was suicidal and was never coming back. Jackson’s lawyers fought to keep the civil suit from going forward, arguing that Jackson should not have to be deposed until the criminal investigation was completed—it might force him to take the Fifth Amendment. On November 23, however, a California judge ordered that Jackson would have to stand trial in the civil suit whether or not the criminal investigation was completed. Bertram Fields, Jackson’s principal lawyer, blundered by telling the judge that a grand jury was “probably about to indict.” Outside the court, Fields said he had misspoken. For Michael Jackson, the millennium came early.

The child’s case against Michael Jackson: It all started with a car breaking down. In May 1992, Michael Jackson, suddenly stranded, contacted Rent-a-Wreck, L.A.’s hip car-rental agency. The owner called his wife, a beautiful dark-skinned ex-model, and told her to get right over to where the mega-star’s car was stalled before he left the scene. Jamie (not his real name), her 12-year-old son from an earlier marriage, to a Beverly Hills dentist and part-time screenwriter, was, like millions of kids the world over, a big Michael Jackson fan. Jamie had met Jackson in a restaurant when he was five, and had sent him a fan letter. He received in return free tickets to a Jackson concert. Now once again Jamie, with his mother and his six-year-old half-sister, met the mythic, androgynous Jackson, the powerful multimillionaire self-contained entertainment conglomerate, a professional since the age of five.

Even by Hollywood standards, Michael Jackson’s weirdness is legendary, but he has always been protected by the armor of his celebrity. He is such a highly prized corporate moneymaking machine, such a valuable product—albeit one as well-known for the cosmetic alterations that feminized his once much darker Afro-American features as for having the biggest-selling record album of all time—that almost no one, especially those C.E.O.’s and moguls who make millions off him, has ever really questioned his motives: why this reclusive man-child with no known history of romantic relationships prefers to live a fantasy life in the company of children. It took this chance encounter to ruin his carefully honed reputation as the world’s richest Pied Piper, Savior of Children.

Immediately after their meeting, Jackson began calling Jamie almost daily. He was about to launch his first concert tour in four years, to 15 countries, and he did so by grandly announcing the creation of a World Council of Children “to provide children with a forum to express their unique vision for healing the world.” His mission, he said, was to work for all children. “I want to tell the children of the world, You’re all our children, each one of you is my child, and I love you all.” While on tour, Jackson began calling Jamie from different points along the way—the conversations would sometimes last an hour. Jamie, who is fine-boned, delicate, and dark like his mother, and who looks much younger than he is, was thrilled to be the object of attention of his idol.

To those who would build a case against Michael Jackson, these long-distance conversations about video games and Neverland, the mini-Disneyland ranch to which he often retreats with young companions, were the beginning of an overwhelming seduction.

They say, however, that nothing happened right away—if anything, events proceeded as if this relationship were a tender love story. “Michael was in love with the boy,” says Larry Feldman, Jamie’s lawyer. “It was a gentle, soft, caring, warm, sweet relationship”—not the alleged perversion that ended last August when Jamie graphically described, first to a psychiatrist and then to the police, exactly how Jackson had repeatedly sexually molested him. Case No. SC026226, filed September 14 in Los Angeles County Superior Court, a civil suit brought on behalf of Jamie, charges sexual battery, battery, seduction, willful misconduct, intentional infliction of emotional distress, fraud, and negligence. “These sexually offensive contacts include but are not limited to defendant Michael Jackson orally copulating plaintiff, defendant Michael Jackson masturbating plaintiff, defendant Michael Jackson eating the semen of plaintiff, and defendant Michael Jackson having plaintiff fondle and manipulate the breasts and nipples of defendant Michael Jackson while defendant Michael Jackson would masturbate.”

Jackson’s first call inviting Jamie to Neverland, which is in Santa Barbara County, a scenic two-and-a-half-hour drive north of Los Angeles, came two days after the star’s famous interview with Oprah Winfrey aired last February 10. The Oprah interview was the culmination of a three-week global media blitz that had Jackson performing in rapid succession at the Clinton inauguration, at the Super Bowl, and on the widely televised American Music Awards. That first weekend, Jamie, his sister, and his mother slept in the guesthouse, which is so far from the main house, where Jackson sleeps, that paparazzi cannot get the two in the same telephoto lens.

Apart from the private zoo, the giant sundial made of flowers, the merry-go-round that plays “Like a Virgin,” the miniature choochoo train, the hall filled with every video game imaginable, the theater stocked with nearly every film and videocassette ever made for children, the pool, the staff of 56 who cater to their employer’s every whim 24 hours a day, Michael also offered Jamie and his sister a special trip to Toys ‘R’ Us after closing time to select a shopping-cartful of presents. Those were the first of dozens of video games, action figures, watches, jackets, and other delights Michael would lavish on the children. Jamie’s mother eventually got diamonds and rubies as well. Needless to say, when Michael invited the family to his playground again the next weekend, Jamie was eager to return. Like most guests at the ranch, Jamie had to sign a confidentiality agreement that he would not speak to the press or write about anything that went on there. This time, before they returned home, Michael took them in his limo to Disneyland, where they got special treatment.

From that point on, Jamie and his mother and sister spent virtually every weekend with Michael. The mother and her current husband were mostly estranged, and Jamie began to withdraw from everyone else, no longer playing with other kids. Eventually, he wouldn’t speak to his father and six-year-old half-brother, even on the phone. He and Michael were quickly labeled “inseparable.” They played with slingshots and squirt guns. They threw water balloons off the balcony of Michael’s condo in Century City onto passing cars.

In March 1993, Jamie spent four days at Neverland. Eleven-year-old Brett Barnes was also there. He subsequently told KNBC-TV—as did 10-year-old Wade Robson—that he too had slept with Michael, but that nothing had happened: “It’s a huge bed.” Also there that weekend were the Cascio brothers, Eddie and Frank, 9 and 13, who traveled alone with Jackson this fall on his “Dangerous” tour. Michael, Jamie, and the other boys would stay up till all hours, their senses assaulted by music, video games, and films.

On March 28, a private jet was sent to pick up Jamie, his mother and sister, and Jackson at the Santa Monica airport and fly them to Las Vegas, where they stayed in the Michael Jackson Suite at Steve Wynn’s Mirage Hotel. It was the first night Michael and Jamie would share the same bed, Michael wearing sweats, Jamie wearing pajamas. Michael had rented The Exorcist, and Jamie got scared. His mother and sister stayed in another bedroom in the suite. The next night the two wanted to sleep together again. But a confrontation ensued, because Jamie’s mother objected.

At this point, claim insiders who believe the case against Jackson, Michael began to cry, telling Jamie’s mother, “This is about being a family, not making judgments.” He declared his love for each of them and pleaded, “Why don’t you trust me? If we’re a family, you’ve got to think of me as a brother. Why make me feel so bad? This is a bond. It’s not about sex. This is something special.” He then said Jamie could sleep wherever he wanted to. That did it—Jamie’s mother was won over. From that night on, with few exceptions, she allowed 13-year-old Jamie and his 34-year-old rich and powerful friend to share the same bed for more than three months. Michael essentially moved in, and lived with Jamie in one room of the family’s small, unpretentious house in Santa Monica Canyon while his little friend went to school.

Jamie has said that sexual touching began at Neverland in April. It started with cuddling and kisses. Michael began to “rub up against me.” He later allegedly told Jamie that their being together was fated “in the cosmos.” By this time, on visits to the ranch, Jamie stayed in Michael’s bedroom; his mother and sister were still in the guesthouse. Both buildings are locked at night and heavily patrolled by security. Michael’s bedroom is connected by a secret staircase to a special guest room, the Shirley Temple Room. Former employees of the ranch report that many boys were invited to sleep in the Shirley Temple Room, and that they would often find the bed untouched. Jackson has such a penchant for privacy that the floor outside his bedroom is wired so that whenever anyone comes within five feet of the entrance there are dingdong noises.

Over time, Jamie says in a leaked confidential Los Angeles Department of Children’s Services report, Michael graduated to “kissing me on the mouth… . One time he was kissing me and he put his tongue in my mouth and I said, ‘Don’t do that.’ … He started crying… . I guess he tried to make me feel guilty.” Michael took the family on a trip to Disney World in Florida and “continued to rub up against me quite often,” Jamie said.

In May, Jackson and his adopted family jetted to Monaco to the World Music Awards, where Jamie and his sister were widely photographed, usually beside Michael at Prince Albert’s table or on Michael’s lap. Most 13-year-old boys don’t spend hours being held on men’s laps, but people at the table guessed that Jamie, who was dressed identically like Jackson, was no more than 9 or 10.

“The little boy was loving every minute of it, getting so much attention,” said a woman who was there. Jackson, heavily made up as usual with white pancake, wore a hat and mirrored glasses to shield his eyes, and covered his nose and mouth with his hand. “His nose looked like a wax model with most of the wax melted away,” the woman said. He barely spoke to anyone other than Jamie and his sister, and drank only Évian water which his bodyguard poured, even then first wiping the glass with his handkerchief. At one point Jackson sent the mother and two friends off in a limousine with a lot of cash and credit cards and told them to buy whatever they wanted.

According to the Department of Children’s Services report, Jamie said things “really got out of hand” in Monaco. “Minor stated Mr. Jackson told him that Mr. Jackson’s cousin masturbated in front of him and that masturbation was a wonderful thing. He coerced minor to bathe with him and later, while laying next to each other in bed, Mr. Jackson put his hand … under minor’s shorts and masturbated minor until minor had orgasm at which point Mr. Jackson cleaned the semen with a tissue saying ‘Wasn’t that good?’ This occurred several times; however, Mr. Jackson began eating minor’s semen, then ‘began masturbating me with his mouth.’ Minor denies ever oral copulating Mr. Jackson or any anal intercourse.”

The family flew home via Paris and Euro Disneyland. They made a further trip to Disney World in Florida, which Jamie recounted to the Department of Children’s Services. “At the end he [Mr. Jackson] had me suck on one of his nipples and twist the other while he [Mr. Jackson] masturbated himself.

“Minor stated Mr. Jackson told minor that minor would go to Juvenile Hall if he told and that they’d both be in trouble. Minor also said Mr. Jackson told him about other boys he had ‘done this with’ but he didn’t go as far with ‘them.’ [Jamie gave authorities the names of four other boys Michael allegedly told him about. Macaulay Culkin’s name appeared in the report, but he has denied any wrongdoing on the part of Jackson.] Minor stated Mr. Jackson tried to make him hate his mo. and fa. so that he could only go to Mr. Jackson.”

With Michael looming as the dominating presence in his life, Jamie began missing many visitations he would ordinarily have had with his father, the Beverly Hills dentist, who is remarried and has a son with his current wife. In the beginning, patients say, the doctor would brag about his son’s friendship with Jackson. The dentist, who had sold one screenplay, seemed eager to continue in show business, and Jamie, who had given him the idea for the screenplay, which was made into a movie, wanted to be a director. The dentist seemed pleased that Michael and Jamie were going to spend five days together at his house, sleeping in a bedroom they would share with Jamie’s half-brother.

Then Jamie’s father saw Jackson and Jamie in bed together. They were fully clothed, but his suspicions were aroused. Michael and Jamie told him, he has said, that they couldn’t stand Jamie’s mother, and that she hated his wife. They seemed to be playing the parents off against one another. Jamie’s father eventually came to believe that because of Michael “there is no family anymore.” Jamie’s mother, with whom the dentist had always enjoyed a friendly relationship, scoffed at his concerns.

In early June, the father saw his ex-wife and their son at a school graduation and angrily demanded, “What’s going on with Michael?” They argued, and the father did not see his son again until mid-July. By then he was feeling desperate, since he knew that his ex-wife was planning to take Jamie out of school so that they could go with Michael and a tutor on the “Dangerous” tour in the fall. One day the father broke down and began to cry while treating a patient who happened to be a Beverly Hills lawyer: Barry Rothman.

Rothman agreed to represent the dentist, whose relations with his ex-wife had become acrimonious. A custody battle was brewing, and legally the father was not in a strong position: he had never paid Jamie’s mother child support, and he owed $68,000. When the father became more and more irate and demanded a meeting, the mother confided in Jackson, who in turn called his lawyer, Bertram Fields, to intervene. Fields did so aggressively, even though minor custody disputes are hardly what he, as one of show business’s most visible litigators, normally gets paid $500 an hour for. Fields called in private investigator/negotiator/forensic audio specialist Anthony Pellicano.

If you’re on the side he’s against, the flamboyant Pellicano, who also writes on the side, is a goon and a bully who fights dirty. If he’s on your side, he is an invaluable ally, a trusted adviser, a canny investigator. He is most often called in when there is deep doo-doo all over that needs to be avoided or slung in the opposite direction. In this case, Pellicano soon became a major player. “If this is such an innocent relationship,” asks Larry Feldman, “why have the likes of Fields or Pellicano?”

On July 9, Jamie’s mother and stepfather met with Fields and Pellicano in Pellicano’s office, on Sunset Strip. After listening to long conversations which the stepfather had secretly taped of himself and Jamie’s father concerning the father’s suspicions about Michael, Pellicano drove over to Jackson’s Century City condominium, where Jamie and his sister were visiting. He questioned Jamie alone for about 45 minutes as to whether anything sexual was going on between Michael and him. Jamie said no.

Meanwhile, Jamie’s father, through his attorney, went to a Beverly Hills psychiatrist, and, without disclosing any names, posed to him as a hypothetical situation the relationship of his son with Jackson, including mention of what the psychiatrist called Jamie’s mother’s “condoning attitude.” He wanted to know if his son might be the victim of child abuse. In a written reply, the psychiatrist reiterated the presented facts, including: “The child’s mother has received numerous and substantial gifts both monetary and material from the adult male.” He characterized the “13-year-old male (the child)”—whose relationship with an “idolized male who is more than 20 years his senior, [and] a celebrity of some sort,” is described as “inseparable”—as being “at risk.” “Events as presented above provide the basis for the conclusion that reasonable suspicion would exist that sexual abuse may have occurred.” The psychiatrist also concluded that “psychotherapeutic intervention” was indicated for everyone involved.

Such would not be the case. Instead, the fighting continued. The father kept demanding a meeting with Jackson, and Rothman suggested to Fields that serious criminal conduct had occurred. The father had repeatedly threatened on tape that he had incriminating evidence against Jackson. On July 11 , Fields, acting as an “intermediary” between the father and mother, ensured that Jamie would be given to his father for one week’s visitation. During the course of that week, Jamie’s side alleges, Jamie admitted to his father that sexual touching had occurred between him and Michael. The father, convinced that his son had been “brainwashed,” refused to give Jamie back and again demanded a meeting with Jackson. On July 12, the mother signed an agreement stating she would not take the boy out of Los Angeles County without the father’s consent. That wasn’t enough for the father, however, and the mother began taking legal steps through her lawyer, Michael Freeman, to force the father to give Jamie back. The father, meanwhile, repeatedly threatened to go public with his information.

Fields, at this point, stepped aside and “let Anthony deal with it.” On August 4, a meeting of Jamie and his father with Jackson and Pellicano took place on the top floor of the Westwood Marquis Hotel. The only thing the two sides agree on is that the father read Jackson parts of the criminal code about reporting child abuse. Money was never mentioned, although Fields and Pellicano, who say they suspected extortion from the beginning, were constantly asking the father and Rothman what it was they wanted.

That same night Pellicano and Rothman got together in Rothman’s office, and Pellicano heard for the first time what Jamie’s father did want: $20 million (for a trust fund, Jamie’s camp says, to be set aside for Jamie’s use only). Pellicano refused. According to Feldman, “The father might have thought, I could have put a bullet in Michael’s head—that’s what he deserves. I could have run to the D.A. and had this sideshow, or I could’ve tried to punish him financially and get him to go and get help so he wouldn’t do it again—it’s a trade-off.”

After inconclusive phone conversations, a second meeting took place in Rothman’s office on August 13, with Jamie’s father present. Pellicano offered the dentist a $350,000 script deal. He suggested that the father and son could foster their relationship by writing scripts together. The father refused.

On August 16, Michael Freeman, Jamie’s mother’s lawyer, informed Rothman that he would be filing papers early the next day that would compel the father to turn over the boy by seven p.m. Rothman asked for time to inform the father, who was performing eight-hour dental surgery. Freeman refused.

On August 17 came the dénouement. Jamie’s father, desperate that he would lose his son, made an early-morning appointment with the psychiatrist to whom he had posed the hypothetical situation: Dr. Mathis Abrams. During a nearly three-hour session, Jamie told Dr. Abrams for the first time the full extent of his alleged sexual relations with Jackson. By California law, such an accusation must be reported to the appropriate authorities, which automatically triggers an investigation. A police sergeant and a social worker from the Department of Children’s Services interviewed Jamie and found that his story was consistent. The therapist told the authorities that he felt the boy was telling the truth.

Michael Freeman, meanwhile, had filed the custody papers and obtained a court order to have Jamie returned to his mother by seven p.m. But that was held in abeyance by the psychiatrist’s reporting of the alleged abuse. Jamie also said that, the week before, his mother had come to get him for lunch and informed him that she was taking him out of the state until the “investigation was completed.” He ran away from her and requested that he be allowed to continue to live with his father. He told authorities that his mother liked the “glitzy life,” and that he was afraid she would allow Jackson to see him again. Jamie also told police that he was glad his father had finally “brought all of this out in the open”; he was ashamed and embarrassed but relieved. When authorities told Jamie’s mother what he had told them about Jackson, she reportedly broke down and said she couldn’t believe how stupid she had been.

At first Children’s Services wanted to take Jamie into custody. Their report recommended that the mother be questioned about “her ability to protect minor,” and that the father be questioned about the discussion of money to keep the whole thing quiet—which Jamie had also talked about. Ultimately, Jamie was allowed to stay with his father.

Anthony Pellicano had no idea that any of this was going on. He had not heard from Barry Rothman since August 13, when his $350,000 offer was rejected, so while Jamie was in Dr. Abrams’s office telling him about the alleged abuse, Pellicano was calling Rothman, determined, he says, to tape him without his knowing it and get him on the record about the $20 million. Pellicano tried his best to make Rothman admit that he wanted $5 million each for four screenplays, but Rothman avoided discussing the matter. About 11:30 a.m., Rothman faxed Pellicano a letter, formally refusing the $350,000 “to settle and release all civil claims our clients have a right to assert against your client.” Pellicano faxed Rothman a letter back which Jamie’s side characterizes as a “cover your ass” letter: “I do not recognize any civil claims against my client whatsoever. We have not and will not submit to the extortionate attempts you and your client have subjected us to.” That day was the first time the question of extortion was raised.

On August 20, Michael Jackson, who had been informed of Jamie’s charges, left for Asia to continue the “Dangerous” tour, sponsored by Pepsi-Cola. Anthony Pellicano went with him. On August 21 and 22, police executed a search at Neverland and the Century City condo and carted off several boxes of material. The story broke on KNBC’s evening news on August 23. The media war had begun.

Michael Jackson’s defense: “If it’s a 35-year-old pedophile, then it’s obvious why he’s sleeping with little boys. But if it’s Michael Jackson, it doesn’t mean anything,” says Anthony Pellicano. “You could say it’s strange, it’s inappropriate, it’s weird. You can use all the adjectives you want to. But is it criminal? No. Is it immoral? No.” Bert Fields, Jackson’s lawyer, agrees. “Michael never had a childhood. He was on the stage from the time he was five, and while he’s a highly intelligent person, he has a lot of childlike qualities. He really lives the life of a 12-year-old.” Fields believes Michael’s behavior is that of any normal 11- or 12-year-old boy. “One of the things he has done—the things I did when I was 11 or 12, probably all of us did—was to have sleepovers. So he’ll have kids stay over at his ranch or wherever he is. And almost always he has their parents along on all these things.”

Pellicano readily admits that Jackson has shared his bed many times with little boys over the years. “If you hide something like that, then people are going to be even more suspicious, and my view of this whole thing is just to tell the truth. He did sleep in beds with little boys. There’s no question about it. He’s got a gigantic bed.” Pellicano isn’t bothered by admitting that Jackson slept with Jamie at Jamie’s house at least 30 days in a row, either. “They invited Michael to stay there. Michael didn’t crash their house. He didn’t say, ‘I want to stay here.’ They wanted him to stay there.”

According to Pellicano, there was no cause for alarm in Jackson’s having a friend like Jamie. “If Michael has no sexual preference one way or another, male or female, to my knowledge, and the parents of the children are allowing this, you have to look at it in the context—especially at the ranch. They go out and they play and they go on the rides and they have water fights and do all this stuff. And then they kind of like crash. Now, Michael is always fully dressed.” Even at Jamie’s house? “When [Jamie] went to bed, he had pajamas on, and sweats, and Michael had sweats and pajamas on. Michael goes to bed with his hat on. I’m serious.” Adds Pellicano, “It would make you nuts if you didn’t know Michael. It would make you crazy. Not only that—I thought to myself—if a mother or a father doesn’t want this to happen, it’s not going to happen.”

Bert Fields says that he suspected the whole thing was a setup from the beginning. Furthermore, he doesn’t think anyone will come forward to corroborate Jamie’s story. “We’ve talked to every child we know of who knows Michael—and had to go back many, many years—and nobody says anything like this ever happened.” He remembers hearing in early July that Jamie’s father was very angry and was demanding a meeting with Michael, because Jackson called Fields about it. “I stopped Michael from going to a meeting,” Fields says. The next thing Fields did was call Anthony Pellicano to say the father was accusing Michael of molesting Jamie. They then got on a conference call with the mother and stepfather. On that very first call, Fields says, the stepfather told him that he thought the father “wants money.”

Later that day or the next, the stepfather, in an effort to help his wife, secretly recorded three long phone conversations with the father and reported back to Fields and Pellicano. (Ironically, Pellicano distributed the tape to the media to bolster his side, but the tape is crudely edited, full of erasures, and at times actually seems to help the father’s case.) From Jackson’s point of view, the tape would have been deeply disturbing, not only because on it the father threatens to “ruin Michael’s career” and bring him down, but also because he implies that he has the proof to do so: “When the facts are put together, it’s going to be bigger than all of us put together, and the whole thing is going to crash down on everybody and destroy everybody in sight.” Jamie’s father says Michael “is an evil guy. He’s worse than bad, and I have the evidence to prove it.”

Also disturbing, though, is the portrait of the parents and stepfather that emerges from the long conversations the two men have. They have both left Jamie’s mother, who is into “hanging out.” The stepfather is immersed in his business and drops into the house irregularly, leaving the family for several months at a time. The dentist seems clearly anguished that “Michael has broken up the family.” He talks endlessly about the need for communication and blames himself for not intervening sooner in his son’s relationship with Jackson. He alternates between a kind of impotent anxiety and grandiose threats. But there is no specific mention of monetary gain.

On the tape, the stepfather, who appears to be a longtime friend of the father’s, tries to play the mediator when the dentist threatens to ruin Michael, saying that he will “blow the whole thing wide open—I will get everything I want, and they will be destroyed forever. She is going to lose Jamie [bleep, break in tape]. Michael’s career will be over.”

“And does that help Jamie?” the stepfather asks.

“That’s irrelevant to me. The bottom line to me is, yes, his mother is harming him, and Michael is harming him; I can prove that, and I will prove that, and if they force me to go to court about it, I will [bleep] and I will be granted custody, and she will have no rights whatsoever… .

“It cost me tens of thousands of dollars to get the information I got, and you know I don’t have that kind of money… . I’m willing to go down financially.”

“Do you think that’s going to help Jamie?”

“I believe Jamie’s already irreparably harmed.”

“Do you believe that he’s fucking him?”

“I don’t know.”

Later, the father asks the stepfather if he’s ever tried to talk to the mother about this whole issue of Jackson’s coming into their lives. “If Michael Jackson were just some 34-year-old person, would this be happening? No. They’ve been seduced away from the family by power and by money and by this guy’s image. He could be the same person without the power and the money and they wouldn’t even be talking to him.”

The stepfather’s answer is that his major concern has to do with money: “I told her I didn’t want him buying her things in Europe. I gave her some money. When he did buy her things and she told me, I got pissed off at her. That’s it. That’s the whole thing. That’s all we ever talked about.”

After listening to the tape with the mother and stepfather, Fields and Pellicano believed that the father had Jackson spend time at his house only so that he could bug the room the star and Jamie shared. “And Michael, innocent that he was, went over, and I think spent a week at the father’s house in the bedroom with the boy,” says Fields. After being told by Rothman that serious criminal conduct may have occurred, Fields raised that possibility with Jackson. “Michael’s response was completely inconsistent with guilt. When I told him what he said, he was completely unafraid of any tape that might have been made during that week. It was not the attitude of somebody who was worried about what was on the tape.”

Anthony Pellicano took the spin that would become his mantra: “They’re all dysfunctional. You have a dysfunctional father, a dysfunctional stepfather, a dysfunctional mother, and possibly a dysfunctional child.” He also decided to go right over to Jackson’s condo and question Jamie. “I went in there with an attitude that I was not going to prove that Michael was innocent. I was going to prove that Michael was guilty. Because if such a thing could occur—and it never would in a million years—I have to protect my client.”

Pellicano is famous for taping people—often secretly—but he didn’t tape his talk with Jamie. “Absolutely not. You have to understand, that was a whim, and I could have. I had no idea what this boy was going to tell me.”

According to Pellicano, Jamie told him a lot in 45 minutes. “He’s a very bright, articulate, intelligent, manipulative boy.” Pellicano, who has fathered nine children by two wives, says he asked Jamie many sexually specific questions. “And I’m looking dead into his eyes. And I’m watching in his eyes for any sign of fear or anticipation—anything. And I see none,” Pellicano says. “And I keep asking him, ‘Did Michael ever touch you?’ ‘No.’ ‘Did you ever see Michael nude?’ ‘No.’ He laughed about it. He giggled a lot, like it was a funny thing. Michael would never be nude… . ‘Did you and Michael ever masturbate?’ ‘No.’ ‘Did Michael ever masturbate in front of you?’ ‘No.’ ‘Did you guys ever talk about masturbation?’ ‘No.’

“‘So you never saw Michael’s body?’ ‘One time, he lifted up his shirt and he showed me those blotches.'” Then Pellicano asked Jackson to come downstairs. “And I sit Michael next to him and go through exactly the same thing,” he says. Pellicano claims they both maintained that nothing happened, and Jamie began to disparage his father. “He’s talking to me about his father never wanting to let him be a boy and never wanting to let him do the things he wants to do. ‘He wants me to stay in the house and write these screenplays.’ … And he said to me several times during this conversation, ‘He just wants money.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?'” Then, Pellicano claims, Jamie told him the story, confirmed by Michael, that when Michael was over at his father’s house his father told Michael he really didn’t have the room for him to stay there. “Why don’t you build me an addition?” Then he went and checked with the zoning board, and he couldn’t put the addition on, “so he asked Michael just to build him a whole new house.” Larry Feldman, Jamie’s attorney, calls this story “ludicrous and factually incorrect. I checked with the zoning board, and there are no such restrictions.” Pellicano says he also learned that the dentist wanted to close down his practice and get involved in screenplays with Michael.

Jamie’s father was demanding to see him. So Fields worked out a deal—”We can’t have Michael being claimed as the cause of this problem.” Then he left town, putting Pellicano in charge. “Bert gives me an absolute free hand when I’m involved.” Pellicano adds, “This is problem solving. This is what I make my money at. This is why I have the reputation I have, because I solve problems.”

“The next thing we hear is that the father has an opinion from a psychiatrist, and he will not give the boy back,” says Fields. “I take the position I won’t talk to the son of a bitch [Rothman] anymore.” Fields prepared the affidavit to help the mother and her lawyer regain custody. The father was still insisting on a meeting with Jackson, who was “very hurt,” says Pellicano, insisting “Jamie would never do this—his father is making him do this.”

Pellicano’s version of the August 4 meeting differs totally from that of Jamie’s side. Pellicano says that as soon as the father and Jamie walked into the room they both hugged Michael. “He’s shorter than Michael,” Pellicano says of the dentist. “And he’s got his head underneath Michael’s neck, and he kisses Michael, and he’s got his eyes closed.” Pellicano was astounded. “If I believed somebody molested my kid and I got that close to him, I’d be on death row right now.”

The father began to read the psychiatrist’s letter, which cited the criminal statutes that applied to child abuse. “Jamie was looking down, and he pops his head up and looks at Michael like ‘I didn’t say that.’ That kind of look.”

Pellicano said, “You don’t have to recite statutes. I know what the statutes are. Are you accusing Michael?” The dentist answered, “This is all about the molestation of my son.” “What is it exactly that you want?” The father answered that Pellicano had told his lawyer “you would help me do screenplays.” Pellicano denied it, and the father got very angry. According to Pellicano, he pointed his finger at Michael and shouted, “Only he can help me!”

“At this point I never heard any extortion. I never heard any demands. I kept wanting to hear demands.” Michael, meanwhile, was scared. “The father keeps pointing at him: ‘I am going to ruin you! I’m going to take you down!'” Pellicano finally told the father to leave, and the father and son walked out the door.

“Did you tape this meeting?” I asked Pellicano. “No. I don’t want to be in the possession of a tape that has my client on it. I don’t know what anybody’s going to say. And you don’t tape-record something unless you know what’s going on.”

Pellicano was left puzzled. “My wheels are turning. If this is an extortion, how am I going to get them in extortion?”

He called Barry Rothman and told him what had happened. They arranged a meeting immediately in Rothman’s office.

“The doctor wants to close down his dental practice and he wants to write full-time, and what he wants is this,” Rothman supposedly tells Pellicano: “Four movie deals, $5 million each.”

“And I look at him like he’s absolutely crazy. You want $20 million? There’s no fucking way that’s going to happen. I’m not going to pay $20 million—and for what?” Once again, Pellicano says, his mind races: Maybe Rothman is lying—how do I get this on tape? Later, they go back and forth on the telephone and arrange another meeting with the father at Rothman’s office for August 9.

Pellicano claims the dentist tells him that he wants to close his practice and work with Jamie, so Pellicano offers “start-up money. And Rothman chimes in and says, ‘Wait a minute—we’ve already told you what we want.’ Rothman says the $20 million: ‘We want four movie deals, $5 million each.'” Pellicano says he looks the father right in the eye and says, “‘It’s never going to happen. Do you understand me?’ … He goes ballistic.” This time it’s Pellicano who gets thrown out.

On the phone, Pellicano offers Rothman one screenplay “at the going rate of $350,000… . I wanted to get them to accept it. They would take $350,000, they would have a contract, and the whole thing would be over. I would get them out of my life, and that would be it.” “Pellicano was convinced they’d go for some kind of offer, some kind of check, and we’d have them,” says Fields.

But it wasn’t to be. Jackson’s side had apparently overplayed its hand. Since Pellicano never heard back, he called Rothman on the fateful morning of August 17 and secretly tape-recorded their Mamet-esque conversation. By that time, the mother’s lawyer had already been in court, and the motion to return Jamie to her had been granted. Rothman essentially tells Pellicano that the custody motion was a “shitty” thing to do, that the mother is now saying she signed the order not to take Jamie out of L.A. County under duress, and that there is an attempt to try to seal the case, “making reference to a third-party celebrity with a high profile who doesn’t want certain things divulged.” Pellicano pleads ignorance.

The $350,000 offer is rejected, Rothman says, because Pellicano originally offered a three-picture deal at $350,000 each, and then he backed down. Rothman says, “You had a discomfort level offering three based on his volatility. O.K., that’s what you told me.”

“Look, we’re still at this deal now if you’re telling me… ,” says Pellicano.

“I just told you why it won’t be accepted, and it can’t be, because you offered three to begin with, and he feels he’s being slapped on the wrist for an emotional response regarding his child.”

Moments later, Pellicano vainly tries to raise the subject of the $20 million: “Listen, the reason I said no to the deal in the office is that he asked for $5 million per year.”

Rothman counters, “That’s not … We’re past that point.”

“Twenty million dollars—” Pellicano persists.

“We’re past that point.”

But Pellicano won’t give up, and Rothman, who still seems eager for a three-picture deal, says, “You sat across the table from him and said, ‘It’s not going to be that figure,’ and he said, ‘O.K., what do you have to say?’ That’s what he said.”

“That’s not true!”

“Yes, it is true!”

With that, the deal was off, and Rothman and Pellicano exchanged the faxed letters.

In last month’s Vanity Fair, Bert Fields told Michael Shnayerson that he thought the father wanted the matter to remain private (“He could hardly hope to collect money after it became public”) and that the father didn’t know that if he took his son to the psychiatrist the therapist would be required by law to report the charges to the police. In an interview for this article, Fields said the opposite. “I believe the father knew that when he went to the therapist it now had to become public. And that was his method of making it public, rather than calling a press conference. They let the therapist do the policing. I can’t believe I would want my child branded for the rest of his life as the child who was molested by Michael Jackson. If it happened to my child, I would want to see the son of a bitch put in jail. It’s much more important to shelter your child, I think.”

Fields thinks that the father concocted the story and convinced his son that this was their one big chance to score. “I don’t believe them.” Then what did happen? “It could have happened many ways. It could be the father coaching the boy, supplemented by the police questioning—it could be a combination of both.” As for the mother and stepfather’s change of heart, Fields has a one-word explanation: “Money.”

Larry Feldman calls the Fields-Pellicano version of events “preposterous,” insisting that it was Pellicano, not the father, who introduced the idea of being paid for screenplays in order to foster a relationship with the boy. “We vehemently deny there is any extortion. At the most there is an attempt to prevent the type of public circus that has occurred,” says the father’s new attorney, Richard Hirsch. “The other side is raising the red herring of extortion, which is not a defense to child molestation.”

“I’m really foggy on this,” says Pellicano, asked why he was unable to prevent the charges from blowing up in public, “because I don’t know what they thought. It doesn’t matter now. Because everything else is history. It’s been on TV.”

Jackson is under criminal investigation in Santa Barbara and Los Angeles counties, but he has not been charged with any crime. A criminal case is far more difficult to prove than a civil action. In a criminal case, the evidence presented must convince all 12 members of the jury beyond a reasonable doubt. A case such as this one, consisting of one person’s word against another’s, with no apparent physical evidence, would be difficult to prove without corroboration. That is what the police have been focusing on—trying to find other children with whom Jackson might have behaved inappropriately.

Suppose there were another child who claimed to have been molested by Jackson. Would his parents subject him and themselves to the media madness of a celebrity trial? One anguished father who had spent considerable time at Neverland called me in despair over the fact that he had ever allowed Jackson to share a bed with his son. He has no proof that anything untoward occurred, but he claims that he himself was molested by an uncle and kept the secret from his parents for 30 years. That knowledge tortures him, because he and his wife are divorced, and he lives so far away that he is rarely able to see his son. He says that his wife, who has custody, told him that if he spoke to the press he would never see his son again. A week later, after talking to his wife, who was in contact with Jackson’s side, he called again, eager to give me a quote in favor of Michael Jackson. Dealing with these kinds of complicated family histories and emotional flip-flops is part of the normal routine of the law-enforcement officers trying to investigate the criminal case.

In a civil case, however, a jury’s decision need not be unanimous, and jurors have only to find that a preponderance of the evidence favors one side—”probably” is good enough. The major difference is that a criminal charge can send a person to jail. In a civil case, the successful plaintiff receives only monetary damages. If the jury finds Michael Jackson liable in the civil suit, he may never have to do anything more than pay up.

Is it likely that any jury will put a mega-star of Jackson’s magnitude behind bars? “The celebrityhood of this will affect every aspect of the investigation and prosecution. It puts pressure on the police; it puts pressure on the D.A.; it changes everything in a trial—it introduces an x factor,” says former Los Angeles district attorney Ira Reiner. “It usually helps the defendant. Juries are starstruck like people generally, and like to be friends of celebrities. It’s not impossible, but it’s extremely difficult, to convict celebrities of crimes.”

Jackson’s lawyers lost their big battle to keep him from being questioned in the civil suit while the criminal investigation is going on. Over the vociferous objections of Larry Feldman, Jackson’s attorneys had petitioned to have the civil action postponed for up to six years while the criminal statute of limitations ran out. On November 23, however, a Superior Court judge in Los Angeles denied that request and set a trial date for March 21. Now Jackson is faced with perhaps having to take the Fifth Amendment in the civil suit, which would not look good.

Feldman emphasized that getting closure for Jamie was critical: “The longer the court case lingers, the longer it takes to begin the healing process.” Not only that, minors have a tendency to forget things: “I’m trying to get him to remember what Michael Jackson’s penis looks like while his therapist is trying to get him to forget it.”

In the course of the hearing, Bert Fields, Jackson’s own lawyer, misinterpreting information hastily given to him by Jackson’s criminal attorney, Howard Weitzman, told the judge that a grand jury in Santa Barbara had issued two subpoenas for witnesses, adding, “You can’t get closer to an indictment than that.” Weitzman appeared amazed at this disclosure; he later contradicted Fields, and within 48 hours Fields was no longer solely in charge of the civil case. Fields has always maintained that a criminal trial for Jackson could be fatal: “The stakes are going to jail and ruining his life, and his life is essentially over if he’s charged and convicted.”

In ruling in Jamie’s favor, the judge honored the California law granting injured minors a speedy trial: “It’s a tough little statute.”

Once a trial date had been set, speculation grew that Jackson would never come back. “He hasn’t sent any money out of the country,” says Fields. “He isn’t moving to Switzerland. He plans to come back to testify.”

On Thursday, November 18, according to Eddie Reynoza, a film and TV actor who was a featured dancer on the “Thriller” video and became a close friend of Michael Jackson’s, a despondent Jackson called him from Switzerland and told him, “I’m never coming back. All my money is being taken over here. We’re cleaning out all my assets, my accounts. I’m selling all my holdings.”

Reynoza, who says he taped a 14-minute conversation with Jackson, says the star “is going from house to house. He’s got a lot of influential friends with houses who are hiding him.” He describes Jackson as “a mess,” although Jackson continues to protest his innocence. Reynoza quotes Jackson as saying, “My lawyers are going to get me out of it. It’s nothing but scandal. They want my money… . I wake up every day and think I’m in hell. I don’t even want to be alive… . I can’t come back and face that. I can’t, I can’t, I can’t.”

Reynoza doesn’t believe Jackson is innocent. “He’s had little boys around for nine years straight, 24 hours around the clock. People in show business couldn’t understand how long it took to get the talk going. The public is 100 years behind on this.” Reynoza acknowledges, however, that people close to the star “looked the other way. They were afraid of being fired.” As for the children’s parents, Reynoza claims that some of them, like Jackson employees, were showered with gifts. “He would buy five Cadillacs at one time. He gives homes, Jaguars, Cadillacs, trips for their birthdays—like a fairy tale out of the movies.”

I asked Reynoza what Jackson is like. He said that they were close for about three years, and then he just got too “weird and freaky… . He’s worried about his face.” Although Jackson admits to only two nose jobs, Reynoza says, “The whole inside of his face is artificial implants. He told me, ‘I can’t go out in the sun. My face would fall off.'”

Reynoza believes that Jackson’s drug abuse is the first step in an escalating series of medical roadblocks. “There’s no way in hell he’s going to appear at a trial with that little boy. He’ll end up in a mental hospital. Next thing will be a nervous breakdown. Don’t be surprised… . You’re going to see a lot more of his people quitting. They don’t want to get involved in all the media.”

The man on the telephone, Paul Barresi, former porn star, personal trainer, police informant, and hustler, sounded outraged. “All these people coming out of the woodwork, screaming for the sake of morality and asking for thousands of dollars! Well, society is responsible—it thrives on the repugnant. The tabloids pay thousands!” He should know. He was selling the same story about Michael Jackson and little boys at Neverland to four British tabloids more or less simultaneously. He had also betrayed the people who had asked him to put them in contact with the tabloids by secretly tape-recording them, photographing them, and giving their names to the police. Now he wondered if Vanity Fair was interested in buying their/his story.

“They” are a French couple, Philippe and Stella Lemarque, who cooked at Neverland for nearly a year before they were dismissed, and who say they were eyewitnesses to scenes in which Michael Jackson took sexual advantage of young guests, specifically Macaulay Culkin, who has denied that anything went on between him and Michael. The Lemarques described on tape Jackson’s alleged modus operandi: keeping the kids up all night with sound-and-light shows, games, and videos until they were so overstimulated that they barely noticed his fondling. Through Barresi, the Lemarques had tried to sell their story a few years ago to the National Enquirer for $100,000, but were told that it would take too much investigation to prove and was therefore legally tricky. But now that Jamie’s charges had broken, they were out hawking again, and they had upped their price to $500,000.

Barresi told me he thought the Lemarques were being greedy—they could easily get $100,000 now, and he would take 10 percent. When I told him that Vanity Fair doesn’t pay sources, he said, “Why don’t you and I do the story, split the fee, and not tell anybody?” He didn’t take my rejection personally.

We met for lunch in Beverly Hills, and he told me he was furious at Kevin Smith of Splash News Service. I’d never heard of Splash, but I soon found out that it is the hot new packager of stories and pictures in the profitable and ever growing celebrity-gossip mill. About a year and a half ago, 27-year-old Smith and his 29-year-old buddy Gary Morgan, both British-tabloid vets, became Los Angeles’s first official tabloid brokers—a clearinghouse for anyone with inside dirt or otherwise about the stars. “People think it’s completely normal to be paid for stories,” Morgan told me later, “and more so in Hollywood, because in Hollywood basically everyone is out to screw everyone else and make a buck.”

Barresi had contacted the Globe in London and was on hold for $15,000 from them for a few days when he got impatient and went to Kevin Smith. He faxed Smith his story, and Smith placed it for $2,400 with the London Mirror. Then Barresi heard from the Globe that it was a go, so he told Smith to stop the deal with the Mirror. Smith’s failure to prevent the Mirror (JACKO’S NEW HOME ALONE SLUR) from scooping the Globe (PETER PAN OR PERVERT—WE CAUGHT JACKSON ABUSING CHILD STAR) enraged Barresi. The Globe still paid him, but the Mirror didn’t.

The Mirror’s recalcitrance prompted Barresi to arrive at the Splash office, Smith says, with a gun and a huge bodyguard. Smith hastily placed a call to the Mirror and assured Barresi he would be paid $1,000. Even so, Barresi felt violated. He fired off a letter complaining about Smith to the Los Angeles Better Business Bureau.

Barresi, who eventually made $23,500 off the story, gave me transcripts of the tapes he had also given to the police and the D.A. The transcripts were carefully annotated as to “inconsistency”: for example, when the Lemarques were asking $100,000, according to Barresi, Jackson’s hand was on the outside of Macaulay Culkin’s pants; when the price rose to $500,000, the hand was inside.

A few weeks later, Barresi called to say that he had decided to pass on his information to Anthony Pellicano. As a fellow Sicilian, Barresi said, he felt simpatico with Pellicano and admired his handiwork. “What he’s doing is painting a clear picture of a dysfunctional family.” The sex-industry veteran Barresi saw the milieu of Neverland as “a perfect situation for a pedophile. Michael Jackson is able to have that fantasyland and could overwhelm kids from dysfunctional families; they’re perfect prey.” Barresi wanted to make one thing clear, however: “I take no sides. I’m in this strictly for the money.”

Pellicano suspects that Splash knew the original source of the leak of the highly confidential Department of Children’s Services report, which had actually been given first to Diane Dimond of Hard Copy, but which found its way to Splash so soon after that that because of the time difference between England and California, Splash’s buyer, The Sun in London, could trumpet a world exclusive: JACKO USED ME AS SEX TOY. Splash won’t reveal how much it paid for the document—guessers say in the $30,000 range—but it was able to sell the report, whose leak prompted a police investigation, not only in England but also in France, Germany, and Australia. Revenues from the report made up a tidy part of the $100,000 Splash has reaped so far on the Michael Jackson story.

“I don’t have any great moral problems paying for stories. If that’s what it takes, so be it,” says Smith. “If you don’t pay for stories, there’s no incentive for people to come forward. That’s a form of censorship, because the news doesn’t get out.” Splash was able to be first to confirm that Michael Jackson had been named in the custody fight between Jamie’s parents by paying “a regular contact” for original court documents (the theft of which may be a felony).

One unfortunate result of the insatiable media lust was that within days Jamie’s real name and picture were appearing in tabloids around the world.

The day I visited the Splash office, they were tracking down people who had been with River Phoenix several nights earlier when he collapsed of a drug overdose outside a club. “Pictures of a last night with River Phoenix in the nightclub and then in his dying throes—its worth could be untold: a quarter of a million dollars,” said Smith. As for the Michael Jackson story, Splash is confident it has everyone else beat. “People at The New York Times haven’t got the resources of an outfit like us,” Kevin Smith boasted. “Four people working flat out on that story. A New York Times reporter hasn’t got a chance. Also, we got money to throw around. So if a Times reporter says, ‘Give me a story,’ they say, ‘No way.'” What about the L.A. Times? I asked. Smith flashed me a look that said, You’ve got to be kidding.

It wasn’t until August 26 that the story that was mesmerizing the world made page one in Michael Jackson’s hometown, and then, thanks to Pellicano and Jackson’s criminal attorney, Howard Weitzman, the first two days’ coverage in the L.A. Times played up the alleged extortion more than the molestation charges. Only on the third day did the Times finally get around to publishing a response from the police as to whether anyone from Jackson’s camp had ever reported any extortion attempt to them. No one had. Even then, the paper made only slighting mention of the Department of Children’s Services report. The paper did report that Jesse Jackson had urged the Times to use more restraint concerning these child-molestation accusations. During the whole month of October, the Times, which has never been aggressive in its reporting on the Hollywood community, ran no stories on the case. A lot of people simply did not want to believe that Michael Jackson could molest little boys, and the tepid Establishment-press coverage reflected the public’s repugnance and ambivalence.

As much as in any political campaign, media manipulation and spin are crucial in a volatile case like this. Pellicano worked tirelessly to shape the coverage, with mixed results. Early on, in his most controversial action, Pellicano introduced to the TV news cameras two young boys who said that they were close friends of Michael Jackson’s and had shared the same bed with him, but that he had never done anything to them. Many people then thought that Pellicano’s effort to clear Jackson had backfired. “Do you know an adult now who is not absolutely convinced that Michael Jackson did it?” said a prominent criminal attorney. “Pellicano ruined it.”

Anthony Pellicano’s greatest strength seems to lie in getting people not to talk. Larry Feldman charges that Jackson’s side has deliberately used Pellicano “to be out front and make slanderous charges about [Jamie] and his parents.” He further states in court documents: “Muzzling independent witnesses, while allowing defendant’s investigator to say anything he wants in a declaration for the press, is not justice.”

Cabell Bruce, a producer for Hard Copy, tells of going up to the front porch of a woman who works at Neverland and trying to talk to her. “She literally started shaking, her eyes filled with tears, and all she could say was ‘Call Mr. Pellicano.'” Diane Dimond of Hard Copy complains that every time she finds a source who has been close to Michael Jackson the response is “Mr. Pellicano has asked us not to say anything.”

Pellicano went as far as to offer to pay Kevin Smith to tell him who had leaked the Department of Children’s Services report to Splash. When Smith refused, Pellicano pointedly said, “You’re not even a citizen” and “I don’t want anyone to get hurt in all this.” There were also reports that Jamie’s father had found a bug on his home phone, and was roughed up at his office. Pellicano denies that he had anything to do with this, saying, “If I had wanted him roughed up, he would have been roughed up.”

Diane Dimond, who along with local KNBC has broken more new developments in this case than anyone else, says she has received messages via other reporters from Pellicano: “Tell Diane Dimond I’m watching her.” “Tell her I hope her health is good.” Pellicano denies any threats.

Jamie’s side also had spin problems at first. The flamboyant feminist attorney Gloria Allred, who briefly represented the boy, promptly called a press conference and announced that her little client was willing to come forward and tell his story. The horrified parents then hired the unimpeachable Feldman, a past president of the L.A. County Bar Association and the L.A. Trial Lawyers’ Association, whose lawyer wife works with sexually abused people. He fired Allred by letter and warned her that if she talked about the case she could be disciplined by the California bar. Gloria Allred left one lasting legacy for the public, however. It was she who raised the question “Why is Michael Jackson, an adult, repeatedly sleeping in the same bed with a young boy?”

In Manila, Mark and Faye Quindoy, a Filipino couple who had managed the Neverland estate, popped up. They were questioned by California police and promised to testify against Michael Jackson. The Quindoys, who say they are suing Jackson for back pay (the amount varies in their statements) and Pellicano for slander (he called them ”cockroaches and failed extortionists”), called two press conferences. They also alleged sexual abuse of children on Jackson’s part; they said they had quit on moral grounds, but they, too, it turned out, wanted money for their story. Mark Quindoy, a lawyer, held a diary up before the cameras. He said he had made detailed notations of what he saw every day at Neverland. Stars on the pages, he said, meant instances of abuse.

I managed to obtain the Quindoys’ Manila phone number without going through their U.S. representative, a woman who works as a private investigator, a tabloid reporter, and their agent on the side. Mark Quindoy and his wife supported many of the things the Lemarques alleged: that Jackson chose one boy at a time, that kids were assaulted with sounds and lights, and that lewd things went on right under the parents’ noses. They did not go to the police, they said, because “we were just witnesses—we were not victims.” They knew the boy whose father had called me in despair. They remembered that his mother would leave the boy with Jackson for “three or four weeks” at a time, and claimed she would cry, “My son has been kidnapped.”

Geraldo Rivera confirmed through a member of his staff that the Quindoys had disclosed to him these same allegations about Jackson at the time they appeared on his show Now It Can Be Told a year and a half ago. But on-camera they gave no hint of any of this. The reason was that they wanted to be paid $25,000.

Given all these bad reports about Jackson, one might assume that the public would be barraged with a resounding campaign for Michael Jackson by his Hollywood friends. With the exception of two statements by Elizabeth Taylor and a few brief unsigned ones from his record company, Sony, the silence has been deafening—from his manager, Sandy Gallin; from his powerful movie agency, CAA; from his dear friends David Geffen, Michael Milken, Steve Wynn, and Diana Ross.

In September, and again in November, Michael’s brother Jermaine and their mother, Katherine, told the press that the allegations were false. Sister La Toya, on the Today show, said that she hoped the allegations weren’t true. Her husband-manager let it be known that her price for talking to the tabloids ranged from $25,000 to $40,000. “Every single person I’ve contacted on Jackson’s side or in his family has wanted money,” says Diane Dimond. “They say, ‘I’d like to tell you something about Michael. He’s a dear sweet boy, and for $5,000 I’ll come on and tell you this.’ It absolutely has impeded me from presenting a full Jackson side of the story.”

Most surprising was the unsolicited proposition Hard Copy got from a representative of Michael Jackson’s father. For $150,000 Joe Jackson would appear on the show to talk about Michael’s troubles. The price quickly dropped to $50,000, but negotiations broke down because the show wanted Katherine Jackson too, and her husband couldn’t guarantee her signature on a contract. The relationship between father and son had come down to a tabloid-TV deal.

Meanwhile, the family, ever ready to cash in on Michael, was planning a $6 million TV extravaganza, The Jackson Family Honors, and counting on their distant son and brother to show up and perform with them in Atlantic City on December 11. It was all to be televised on NBC—although those who know the tortured family history might argue that receiving an honor from the Jacksons is akin to being crowned Miss America by Heidi Fleiss. The TV special was to be the launch of their latest moneymaking plan: a series of franchises to market clothes and cartoons taking advantage of Michael’s relationship with children.

Layers deep, there is virtually no one Michael Jackson knows who does not view him as some sort of big-bucks ticket to ride. Certainly in his own twisted family, he has from an early age been leaned on—the adorable little sensitive, effeminate one with the most talent, taught to manipulate the press, even lie about his age as an eight-year-old. Says ABC News Day One correspondent Michel McQueen, who has dealt extensively with Jackson family members, “They think the truth is whatever they can convince someone of.”

Starting in the days with Motown, their early record label, the Jackson 5 were always packaged as God-fearing, all-American, squeaky-clean. But even words such as “dysfunctional,” “ignorant,” “troubled,” and “screwed up” don’t begin to describe what has been presented as the real Jackson-family dynamic: the cruel, violent father, with ambition far beyond his ability to cope, who would rouse his kids out of bed at two a.m. to perform, appear at their windows at night in a werewolf mask, flaunt his out-of-wedlock second family, and tell little Michael that there were people in the audience with guns who wanted to shoot him, and that if he didn’t move onstage they’d find their target; the sweep-everything-under-the-rug-and-prevaricate-about-it mother, a fervent Jehovah’s Witness whom Michael clung to and adored; the various siblings with their multiple marriages and pregnant girlfriends on the side; loose-cannon sister La Toya, with her public allegations of physical and sexual abuse by her father, posing nude in Playboy. The Jacksons alone could provide several straight seasons of Geraldo.

“When the Jacksons, none of whom have much education, became famous in the 70s, there were not that many prominent blacks—there was no Colin Powell, no Maxine Waters, no Walter Washington or David Dinkins to be role models. They were the ones on the cover of Life. They were the people who represented black America,” says McQueen. “But when black America didn’t need to reflect itself in them anymore,” most of the Jacksons could not accept that time had passed them by. Even today, they treat people visiting the family home in Encino (which Michael owns 75 percent of) as if they were visiting the White House. Before McQueen and her ABC crew were allowed to inspect the property, they were asked to put on identifying hospital bracelets provided by Jackson-family security.

Throughout his life, Michael has always been the sensation, the supreme object of attention, despite his parents’ strict insistence on equality among the six brothers and three sisters, despite his father’s beatings to disabuse him of any notion of superiority. He was closest to two of his sisters, Janet and La Toya, and not at all macho like his brothers, but he was the only one who ever stood up to their father, whom he called “the devil.” Conventional wisdom has it that Michael Jackson never had a childhood—that’s why he loves being a child. But a woman who observed him closely during the early years disagrees: “He loves childhood because he was a child star. He loves to remember it. Michael is narcissistic in the extreme.”

Often isolated from other kids when he was growing up, she says, he learned everything he knew from TV, and “everything he saw on television that represented class and glamour was white.” He reportedly recommended that an 11-year-old blond, blue-eyed white boy play him as a child on the recent mini-series The Jacksons: An American Dream and in Pepsi commercials. His isolation, a severe case of teenage acne, and his resentful brothers’ taunts about his “big nose” caused him to insulate himself even further, especially from their sexual exploits with women. One of the most terrifying experiences of his life, apparently, occurred when he was barely a teenager and his brothers threw a willing woman at him. In business, however, he became even at a young age very shrewd and highly competitive, and today he is often described as “cutthroat.” He can read a complex contract and has always taken an active role in managing himself. But his isolation has left him with only a career instead of a life. “Socially, you cannot be with Michael Jackson,” says a recording-industry fixture who knows him very well. “You can if you’re willing to talk about his career. He wouldn’t know what to do at a mixed dinner party.” The woman says, “He’s like a skyscraper built on eggshells.”

Two scenes leap out of J. Randy Taraborrelli’s absorbing unauthorized biography Michael Jackson: The Magic and the Madness. In the first, 14-year-old Michael, who hid behind his strict religion, pleads with an 18-year-old girl backstage after a concert not to go and meet his brother Jackie, then 21. “My brothers, sometimes they don’t treat girls too good. They can be mean. I don’t know why they do these things, but they do. Please, don’t go.” But she does go, and has her first sexual experience. On her way out of the apartment building, she sees Michael pulling up in a white Rolls-Royce. “What did you guys do? … Did you just have sex with my brother?” he demands. When she admits that she did, and even that she wanted to, Michael says, “Why would you want to do that? Don’t ever do that again, O.K.?”

That is the Michael who as far as anyone remembers has had fewer than five dates with women in the last decade, including one with Brooke Shields in 1984 to attend the Grammy Awards (he won eight) and another with Madonna in 1991 to attend the Academy Awards and Swifty Lazar’s party afterward. The Michael who objected to one of his managers, who is openly gay, having his young boyfriend around. The Michael who was extremely close to a gay cousin, who recently died.

The other haunting scene in Taraborrelli’s book is simply eerie: Michael is 19, in New York making The Wiz, on his own for the first time, chatting with teenage fans in the apartment he is sharing with La Toya. “We all sat around and talked about child abuse,” a friend named Theresa, who was there, recalls. “Michael was fascinated with child abuse. He wanted to know everything we girls had ever heard or read about it. He said he liked to read about child abuse as much as he possibly could.”

Taraborrelli does not believe, however, that Michael Jackson has molested anyone, mainly because he is so open in his relationships with children. “If Michael Jackson is guilty of anything, it’s poor judgment. Many people have warned him over the years that this kind of thing could happen. But he’s the type of person you can’t really tell what to do.” Taraborrelli says he researched the biography for 10 years, interviewing hundreds of people both on and off the record. “I was never able to find anyone who had intimate relations with Michael Jackson whom I believed. Fifty claimed to, but I didn’t believe them.”

When Michael finally left home in 1988 at age 29, he had already passed through an intense relationship with the tiny 12-year-old actor Emmanuel Lewis, whom he carried around everywhere like a baby. Taraborrelli reports that the friendship ended shortly after the two checked into a posh L.A. hotel as father and son. On one leg of his 1988 “Bad” tour, according to Taraborrelli, Jackson took along a 10-year-old California boy named Jimmy Safechuck, on whom he showered gifts, and whose parents got a $100,000 Rolls-Royce from Michael. His manager at the time encouraged him to break off the relationship, because it looked so bad.

Instead of “growing up,” since getting out on his own and moving to Neverland, Jackson has seemed to regress to childhood whenever he’s not dealing with the business of maintaining himself as a superstar. Life at Neverland appears to be that of the court of a scared and isolated child emperor who has no idea whom to trust, and to whom no one ever says no. Conversations with a half-dozen people who have lived and worked there reveal that security is so tight that employees are not allowed even to take a walk on the grounds—whether or not Michael is in residence. He calls for food and requires attending 24 hours a day. He often has almost no contact even with such high-powered guests as Marlon Brando and Elizabeth Taylor, who once stayed for three weeks and had dinner with him once. When staff members are hired, they are told immediately never to look Michael Jackson in the eye or try to engage him in conversation. Yvonne Doone, who was a cook there for nine months in 1990, explains why: “Whenever he was in a room, all eyes were always on him, all ears were always on him. He can never be ordinary. He can never be someone else in the room… . He pays other people to supply protection because he can’t trust.” She describes life at Neverland as “a radiating circle of fear.”

“I think he thinks he’s Jesus,” said a Hollywood producer who has known him since childhood. “A lot of his imagery is about Christ. He feels he’s going to save the world through children.” In fact, Jackson has a huge painting hanging on a wall at Neverland depicting the heads of Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, George Washington, and Michael Jackson.

One Hollywood screenwriter remembers that immediately after his baby was born in a Santa Monica hospital a release form was thrust at him. “What’s this?” he asked. “It’s from Michael Jackson,” said the nurse. She explained that Jackson frequented the hospital to stare into the eyes of newborns. “He feels then that he can really see their souls.”

“At Neverland,” says Yvonne Doone, “there’s a special room filled with dozens of $500 dolls, because Michael so much wants to have a little girl someday.”

Although Jackson’s personal wealth is about $150 million, it could be more if he did not indulge himself by spending millions of his own money on his videos and other projects. Last year on his European tour, for example, Jackson arranged to be able to wake up every day and choose which form of transportation to take him to the next destination—a private jet, a private railroad car, or a convoy of buses. The railroad car and buses had to be flown everywhere in a Soviet cargo carrier. “The waste was enormous,” said a tour planner.

Kids at the ranch sometimes seemed overwhelmed by all the things that were thrown at them. One 13-year-old boy risked killing himself, says a woman who worked there, trying to retrieve an Easter egg hidden in a crystal chandelier by jumping off a balustrade. The eggs were filled with $1,000 in bills. “Why would you do that?” the woman asked him. “I’d do anything for money,” the boy replied.

Fame, eccentricity, and money have always shielded Michael Jackson from dealing directly with anything he doesn’t like, and if things don’t go his way he is subject to panic attacks. In the past, according to Randy Taraborrelli, Jackson has been secretly hospitalized several times for such attacks, disguised as respiratory ailments. Taraborrelli says he cannot imagine Jackson withstanding a police interrogation. “I think he’ll just start to cry. He has created his own world so that he never has to deal with ordinary life, and he won’t be able to.”

By November, reality was becoming such a nightmare that Jackson couldn’t go on. It was then, his side argues, he began taking such quantities of painkillers that he couldn’t function. Curiously, the second week in November, while Jackson was performing in Mexico City, his lawyers, who had said there was no way he had time to give Feldman a deposition, insisted he be deposed there in another, copyright case so that he would not have to appear at a trial in Los Angeles in December. Three songwriters were charging that he used their work in creating the songs “The Girl Is Mine,” “Thriller,” and “We Are the World.” Later, two lawyers gave differing statements about Jackson’s behavior during the 10 hours he was being questioned. His side said he was impaired; the other side’s attorney said he was just fine.

Meanwhile, police searched the Jackson-family home in Encino, looking for evidence in the child-abuse case. Among Michael’s things they reportedly found a nude photo of a little boy. Was it that news that so upset him that he called his old friend Elizabeth Taylor for help, or was it the fact that he was next scheduled to play Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, where the police might question him? Amid rumors that he was suicidal, Taylor jetted to his side and in a dramatic late-night heist helped spirit him out of Mexico to an undisclosed clinic somewhere in Europe. Says Pellicano, “I used decoys all over the place.”

By the time Jackson’s attorneys held a press conference the following Monday to reiterate that he was not faking his drug addiction, and that he had every intention of coming back to testify, rumors were rife that Jamie had given the police a description of Jackson’s genitals and that police wanted to examine him. It was true, and by November 19 police, apparently concerned that he might be trying to have the alleged telltale markings altered in Europe, raided both his dermatologist’s and his plastic surgeon’s offices, looking for his medical records. They were gone.

So was a key witness, Norma Staikos, the duenna of Neverland, who had made the arrangements to bring children there. Without informing the police, she left the country for Greece, triggering speculation that she too was on the run. Howard Weitzman said, “I know she’s coming back, and I’ve told this to the police. To use the word ‘flee’ is egregious.”

Those in law-enforcement circles had long believed that there would be no indictment without an airtight case. As evidence piled up, the L.A. District Attorney’s Office informed Weitzman that it wanted to question Jackson. Fields, meanwhile, antagonized authorities by sending a letter to the police commissioner claiming that police were using intimidation and scare tactics with children they were questioning.

Nothing, it seemed, could stop the avalanche of horrific developments. Pepsi had already said that once the “Dangerous” tour was over it no longer had a corporate connection with Jackson. NBC put the Jackson Family Honors special on hold. Jackson had abruptly dropped out from doing the theme song and video for the film Addams Family Values; when the movie was released, there was now a scene in which a kid sees a Michael Jackson poster and recoils in horror. People magazine’s November 29 cover read, MICHAEL JACKSON CRACKS UP.

Out of the blue, just as the judge denied Jackson’s petition to postpone the civil suit, five ex-bodyguards of the Jackson family sued, claiming they had been fired because they knew too much. One reported that Jackson had asked him to destroy a photograph of a nude boy that was in a bathroom in the family home. Fields dismissed the charges as bogus.

About the same time Jackson called Eddie Reynoza, he also called Diana Ross in Las Vegas to declare his innocence. A week later, his brother Jermaine was quoted in the London tabloid Daily Express: “I love him, but you have to wonder if there might not be some truth in it.” Jermaine later denied ever having made the statement.